So you are not quite sure when manual focusing would be a better choice than letting the camera do the work for you? Well hopefully by the end of this blog post you will know what to use and when to use it.

So you are not quite sure when manual focusing would be a better choice than letting the camera do the work for you? Well hopefully by the end of this blog post you will know what to use and when to use it.First off, how does auto focus work? I am glad you asked! Auto focus systems rely on one or more sensors to determine correct focus. Most of the modern DSLR cameras use a through-the-lens optical auto focus sensor that also have a built in light meter. Most DSLR cameras have at least 3 of these sensors which the camera or the user can select. The speed and accuracy of through-the-lens optical auto focusing is now often more precise than what can be achieved manually with an ordinary viewfinder.

The problem arises when the camera's sensors cannot get enough light or when the depth-off-field is too shallow or when the camera cannot keep up with the action So what might some of these situations be?

- Macro Photography

- Portraits

- Low Light Photography

- Action Shots

- Shooting Pictures Through Glass or Fences/Screen

When shooting macro photography (extreme close-ups) most SLR/DSLR cameras have a very hard time finding the correct focus point due to the very shallow depth-of -field. If you try to shoot macro photography using auto focus you would find that the camera would struggle whiring back and forth trying to find a point of focus. When I shoot macro I exclusively manual focus my camera.

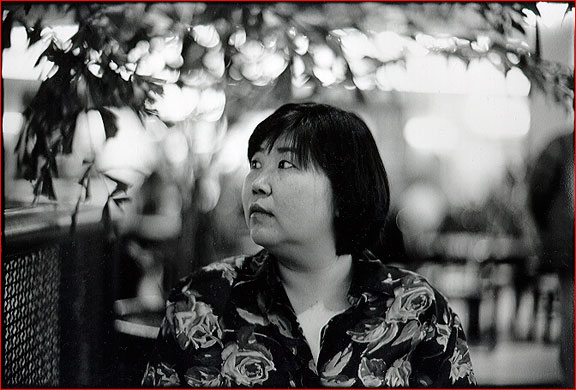

Portraits

When shooting portraits focus needs to be spot on. Most portrait shots require having the subjects eyes in perfect focus and manual focusing will allow you to dial in that focus point.

Low Light Photography

Cameras have a very hard time focusing in low light situations due to the lack of light entering the camera's sensor(s). You’ll know when your camera is struggling using auto focus when every time you go to take a shot the lens will whirl from one end of it’s focusing options to the other and back again before deciding on where to focus.

Action Shots

When shooting fast moving objects your cameras auto focus mode might get confused, even if you are using the continuous focus setting. The best way around this is to use manual focus and prefocus on a point that the subject will move through - and shoot at that point.

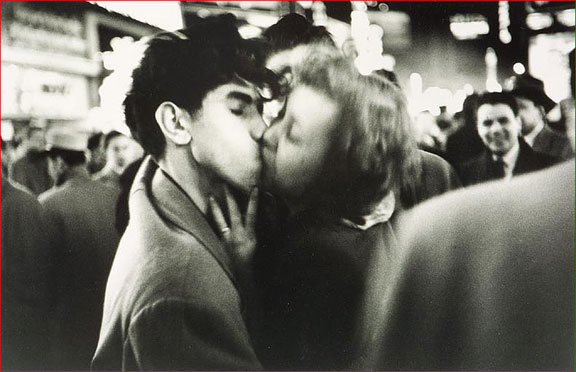

Shooting Pictures Through Glass or Fences/Screens

When shooting through something that may seem like they may not interfere don't be so sure. When using auto focus the camera may want to focus on the nearer point be it glass, fencing, or a screen. To keep the camera from focusing on these items and to be able to get that candid shot use manual focus. It will allow you to tell the camera exactly what you want to be in focus and what you want to be blurred.