I believe that bokeh is best explained in the words of Mike Johnston so please read on.

Bokeh in Pictures

I first learned about "bo-ke" or boke in 1995, from Carl Weese, who learned about it from our mutual friend the oracular and extreme Oren Grad, who holds eight Master's degrees, three Ph.D.s, and an M.D., and who evidently taught himself Japanese so he could read Japanese photo magazines. (Perhaps I exaggerate these facts, but only slightly.) I then commissioned and published three articles about it in the March/April 1997 issue of Photo Techniques back when I was editor — one each by John Kennerdell, who is an American ex-pat living in Bangkok, Oren himself, and Harold Merklinger, a high-ranking research scientist in the Canadian defense establishment. It's one of the few issues of that magazine that sold out. My own contribution was...er, a letter. I decided that people too readily mispronounced "boke," so I added an "h" to the word in our articles, and voilá, "bokeh" was born. A Google search for the word "bokeh" just now resulted in approximately 13,300 hits. Seems the idea's gotten around.

Actually, to be precise, what I had noticed was not just that people mispronounced the word as it was commonly spelled, but that they had a tendency to ridicule it, making lame jokes about it as if it rhymed with "smoke" or "toke" or "joke." Actually, even spelled boke, it is properly pronounced with bo as in bone and ke as in Kenneth, with equal stress on either syllable. It is a Japanese word meaning, roughly, "fuzzy," and it is used to describe old people with cobwebs in their heads among several other things — including the out-of-focus areas of photographs, which, I'm told, might more specifically be referred to as "boke-aji."

One of the curious aspects of the phenomenon for me was that some people then, and some even now, respond to the idea scornfully or even angrily. Is this some sort of insistence on conformity, as if you are supposed to look at certain parts of pictures and not others? I never did know, and I probably never will. (But then, there are a lot of things about my native culture that I will just never understand — for instance, rubber suits as erotic accessories, or why it would occur to anyone to hate black people. What's up with that, anyway? I mean, I certainly know that race hatred exists — I just haven't got the faintest idea why).

Now, I have to admit that I got somewhat obsessed with bokeh after I finally became aware of it. It interested me, in particular, that different lenses render blur in different ways. Even knowing that I take things a bit too far, though, it always seemed strange to me that there are people who don't think it's valid to look at the blurry parts of pictures.

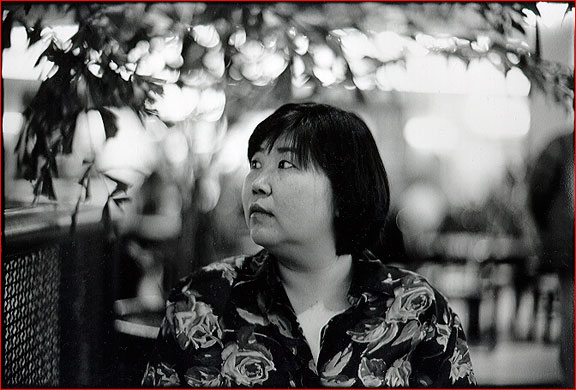

Take this picture by Tony Rowlett, for example. It was made with a Leica Noctilux at a fairly wide aperture. I don't think it's possible to look at this and not get interested in what's going on in the out of focus areas, do you? If you really look at it, there are some pretty amazing abstracted shapes and tones. Does anyone really look at a picture like this and completely ignore all the blurry parts? I doubt it.

The most obvious way bokeh gets into pictures, of course, is simply as background. In Robert Harrington's cruel but beautiful picture here, for instance, most of the area of the picture is occupied by bokeh, even though it has nothing to do with the subject of the picture. The picture might be as good with a plain white or black background. Still, if you just look at the bokeh as it exists, it's hard to deny that the color and brightness of the out of focus parts contribute to the sense of a certain kind of light, and the feeling of the outdoors.

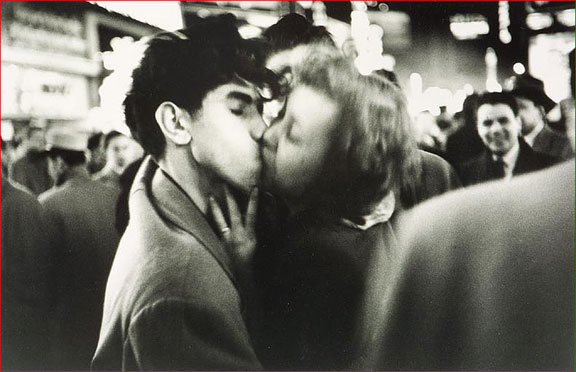

Here's a street shot by the excellent '50s photographer Dan Weiner, who has always been one of my favorites. It shows that motion blur can blend with bokeh in interesting ways. (It also shows just how little sharpness really matters in some pictures.)

Some artists go ahead and use bokeh as an integral part of their subject matter. Kim Kirkpatrick made deft use of it as design, as figuration, and as a way to use color abstractly in a large body of work he made over five or six or so years in the '80s and '90s.

![]()

Fear Not

It's true that some photographers seldom or never take pictures in which anything is not sharp. For them, bokeh is not much of an issue when they're working, although it's still pertinent when they're looking at other peoples' pictures. For the rest of us, well, there's nothing to be scared of. It's just another arrow in the creative quiver. ~ Mike Johnston

No comments:

Post a Comment